Phrase structure rules

Phrase-structure rules are a way to describe a given language's syntax and are closely associated with the early stages of Transformational Grammar[1]. They are used to break down a natural language sentence into its constituent parts (also known as syntactic categories) namely phrasal categories and lexical categories (aka parts of speech). A grammar that uses phrase structure rules is a type of phrase structure grammar - except in computer science, where it is known as just a grammar, usually context-free. Phrase structure rules operate according to the constituency relation and a grammar that employs phrase structures rules is therefore a constituency grammar and as such, it stands in contrast to dependency grammars, which are based on the dependency relation[2]

Contents |

Definition

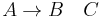

Phrase structure rules are usually of the following form:

meaning that the constituent  is separated into the two subconstituents

is separated into the two subconstituents  and

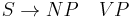

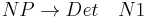

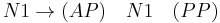

and  . Some further examples for English are as follows:

. Some further examples for English are as follows:

The first rule reads: An S (sentence) consists of an NP (noun phrase) followed by a VP (verb phrase). The second rule reads: A noun phrase consists of a Det (determiner) followed by an N (noun). Some further categories are listed here: AP (adjective phrase), AdvP (adverb phrase), PP (prepositional phrase), etc. Applying the phrase structure rules in a neutral manner, it is possible to generate many proper sentences of English. But it is also quite possible that the rules generate syntactically correct but semantically nonsensical sentences. The following example sentence is notorious in this regard, since it is complete nonsense, even though it is syntactically correct:

This sentence was constructed by Noam Chomsky as an illustration that phrase structure rules are capable of generating syntactically correct but semantically incorrect sentences. Phrase structure rules break sentences down into their constituent parts. These constituents are often represented as tree structures. The tree for Chomsky's famous sentence can be rendered as follows:

A constituent is any word or combination of words that is dominated by a single node. Thus each individual word is a constituent. Further, the subject NP Colorless green ideas, the minor NP green ideas, and the VP sleep furiously are constituents. Phrase structure rules and the tree structures that are associated with them are a form of immediate constituent analysis.

Top down

An important aspect of phrase structure rules is that they view sentence structure from the top down. The category on the left of the arrow is a greater constituent and the immediate constituents to the right of the arrow are lesser constituents. Constituents are successively broken down into their parts as one moves down a list of phrase structure rules for a given sentence. This top-down view of sentence structure stands in contrast to much work done in modern theoretical syntax. In Minimalism[3] for instance, sentence structure is generated from the bottom up. The operation Merge merges smaller constituents to create greater constituents until the greatest constituent (i.e. the sentence) is reached. In this regard, theoretical syntax abandoned phrase structure rules long ago, although their importance for computational linguistics seems to remain intact.

Alternative approaches

Constituency vs. dependency

Phrase structure rules as they are commonly employed result in a view of sentence structure that is constituency-based. Thus grammars that employ phrase structure rules are constituency grammars (=phrase structure grammars), as opposed to dependency grammars[4], which view sentence structure as dependency-based. What this means is that for phrase structure rules to be applicable at all, one has to pursue a constituency-based understanding of sentence structure. The constituency relation is a one-to-one-or-more correspondence. For every word in a sentence, there is at least one node in the syntactic structure that corresponds to that word. The dependency relation, in contrast, is a one-to-one relation; for every word in the sentence, there is exactly one node in the syntactic structure that corresponds to that word. The distinction is illustrated with the following trees:

The constituency tree on the left could be generated by phrase structure rules. The sentence S is broken down into into smaller and smaller constituent parts. The dependency tree on the right could not, in contrast, be generated by phrase structure rules (at least not as they are commonly interpreted).

Representational grammars

A number of representational phrase structure theories of grammar never acknowledged phrase structure rules, but have pursued instead an understanding of sentence structure in terms the notion of schema. Here phrase structures are not derived from rules that combine words, but from the specification or instantiation of syntactic schemata or configurations, often expressing some kind of semantic content independently of the specific words that appear in them. This approach is essentially equivalent to a system of phrase structure rules combined with a noncompositional semantic theory, since grammatical formalisms based on rewriting rules are generally equivalent in power to those based on substitution into schemata.

So in this type of approach, instead of being derived from the application of a number of phrase structure rules, the sentence Colorless green ideas sleep furiously would be generated by filling the words into the slots of a schema having the following structure:

-

- [NP[ADJ N] VP[V] AP[ADV]]

And which would express the following conceptual content:

-

- X DOES Y IN THE MANNER OF Z

Though they are noncompositional, such models are monotonic. This approach is highly developed within Construction grammar[5], and has had some influence in Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar[6] and Lexical functional grammar[7], the latter two clearly qualifying as phrase structure grammars.

Notes

References

- Ágel, V., Ludwig Eichinger, Hans-Werner Eroms, Peter Hellwig, Hans Heringer, and Hennig Lobin (eds.) 2003/6. Dependency and Valency: An International Handbook of Contemporary Research. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Bresnan, Joan 2001. Lexical Functional Syntax.

- Chomsky, Noam 1957. Syntactic Structures. The Hague/Paris: Mouton.

- Chomsky, Noam 1965. Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Chomsky, Noam 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

- Goldberg, Adele 2006. Constructions at Work: The Nature of Generalization in Language. Oxford University Press.

- Pollard, Carl and Ivan Sag 1994. Head-driven phrase structure grammar. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Tesnière, Lucien 1959. Éleménts de syntaxe structurale. Paris: Klincksieck.

See also

- Bare Phrase Structure

- Clause

- Context free grammar

- Dependency grammar

- Extended Backus–Naur Form, the direct equivalent in formal language theory

- ID/LP grammar

- Phrase

- Phrase structure grammar

- Sentence (linguistics)